Washington City, as the District of Columbia was commonly referred to in the mid-nineteenth century, was frequently under threat during the Civil War. The two Battles of Bull Run (Manassas) in July 1861 and August of the following year caused citizens and Union leadership in the city to fear an invasion by “Stonewall” Jackson following these battles that took place only twenty-six miles from the nation’s capital. After the second battle in 1862, Union units such as the 155th Pennsylvania, that had only recently been formed, were quickly sent by rail to Washington to meet any invasion by Confederate forces. In September of that year, General George McClellan was put back in command of the Army of the Potomac with orders to defend Washington. The specters of Robert E. Lee and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson swooping in on a capital with feeble defenses was of growing concern.

While his orders were “command of the fortifications of Washington and all of the troops for the defense of Capital,” McClellan stretched his mission beyond Washington to include wherever he thought Lee’s forces would move. The general’s elastic interpretation of his scope of responsibility concerned official Washington, but the threat of an invasion by the Army of Northern Virginia outweighed concerns over command overreach. In early September, the Confederate threat was shifting from a possible invasion of Washington to the danger posed by Lee’s move into Maryland and, potentially, on to Pennsylvania. By that time, General McClellan had firm control of the Army of the Potomac and a mandate, he believed, to take his army where it was needed to intercept Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Washington City, for the time being, was off the list of immediate concerns.

In the early summer of 1863, a threat to Washington City once again surfaced. Troop movement intelligence from Union cavalry and pressure from civilian leaders in Washington soon convinced General Joseph Hooker, now commander of the Army of the Potomac, that his designs on taking Richmond could wait. Washington, once again, needed protection. Lee’s army was moving north on a relentless path parallel to the Federal capital shielded by the Blue Ridge and South Mountain ranges west of the city.

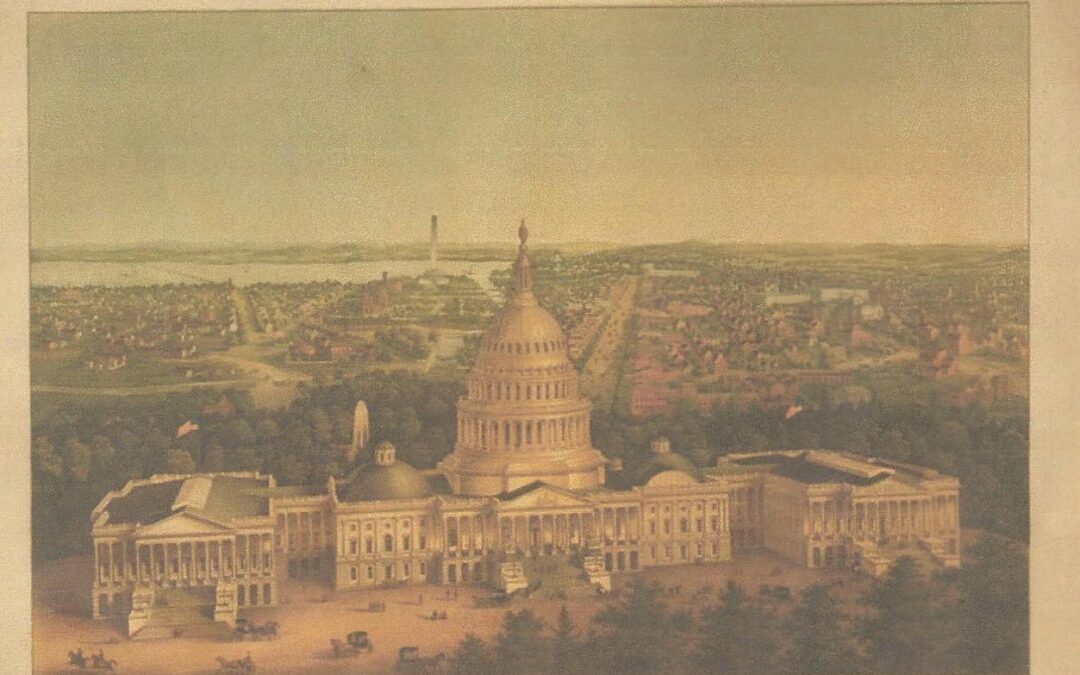

In late June 1863, a specific incident raised Union fears about a Confederate invasion of the capital city. Confederate cavalry General JEB Stuart and his three brigades of cavalry crossed the Potomac River from Virginia and began a brazen foray into Montgomery County Maryland. At one point, the Confederate cavalry units chased a Union wagon train to the outskirts of Washington before turning it around. They seized control of the wagons, their contents, and mules before heading the train north to Pennsylvania. Stuart’s units had come close enough to the District to clearly see the capitol dome before turning around and taking the wagon train north. Had Stuart not had an obligation to join Robert E. Lee’s forces in Pennsylvania, speculation is that Stuart would have continued into Washington City to raid Union stores.

The final Confederate incursion into Washington City occurred in July 1864. Confederate forces numbering 20,000 men under the command of General Jubal Early, assembled in Frederick, Maryland with the intent of driving south to take the Capital City. Their goal was to disrupt the Union government and possibly take senior Union officials hostage. On July 9th, Union General Lew Wallace met the enemy on farmland adjacent to the Monocacy River in Maryland. The fighting resulted in approximately 2,000 Union casualties (compared to 700 Confederate casualties). While the Union lost the battle the day of fighting delayed Early’s march into Washington and exhausted his men. According to one historian: “The rugged nineteen-mile march on the hot and grimy Sabbath had nearly broken his [Early’s] army.”

During the delay in Early’s forces moving south toward Washington from Monocacy, Union forces protecting Washington were supplemented, including reinforcements from the XIX and VI Corps. Fighting was focused at Fort Stevens in the District, where even President Lincoln made an appearance and was nearly hit by enemy fire before a Union officer encouraged the Chief Executive to take cover. By the afternoon of July 11, Union forces had driven back the enemy and the Confederate raid collapsed. The Rebel forces withdrew from Washington ending the final attempt of Confederate forces to take the Union capital by force.

Capitol image courtesy of the Library of Congress collection

Sources include: Your Brother in Arms: A Union Soldier’s Odyssey by Robert C . Plumb and The Day Lincoln Was Almost Shot: The Fort Stevens Story by Benjamin Franklin Cooling III.

Recent Comments