“When the Civil War ended, woman was at least fifty years in advance of the normal position which confirmed peace would have assigned her.”

Clara Barton

The seed for women’s suffrage was planted in the small upstate New York town of Seneca Falls thirteen years prior to the American Civil War. There, in 1848, Elizabeth Cady Stanton drafted the Declaration of Rights and Sentiments that would become the first detailed articulation of women’s rights in the United States. The three hundred persons in attendance voted unanimously to accept the document. Stanton spelled out women’s natural rights in the areas of legal standing, property rights, employment practices, fair pay, access to education, and – most radical at the time – the right to “elective franchise,” or the right to vote.

The Seneca Falls initiative started the movement toward achieving women’s rights, but the Civil War caused advocates to set aside their efforts while the war took precedence. Despite the war’s five-year delay in advancing women’s rights, thanks to the Seneca Falls meeting, women had developed the necessary skills that would be used when the war was over. Seneca Falls became an important model for organizing activities such as managing operating budgets, developing and distributing petitions, and engaging the print media to communicate their positions. All of these skills would prove vitally important in the success of the women’s rights movement in the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-centuries. Many notable women strengthened their advocacy skills during the Civil War and once the war was over, they shifted their focus to women’s issues.

Harriet Tubman’s priorities and finances usually led her post-war efforts to focus on local community efforts, however, her friend Lucretia Mott eventually encouraged Tubman’s involvement with Susan B. Anthony’s National Woman Suffrage Association. In November 1896, Anthony escorted Tubman to the podium to speak at a women’s suffrage convention in Rochester, New York. Tubman addressed the group on her Underground Railroad activities. While not covering the subject of woman’s suffrage per se, it was clear to all present that Tubman was the embodiment of the strong, independent woman who had achieved heroic feats on her own against overwhelming odds. She was the model feminist with exceptional bona fides. In this way she endorsed women’s rights without addressing the subject in detail.

Harriet Beecher Stowe’s guiding beacons for women’s rights and suffrage were the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution. Writing in the Hearth and Home periodical, Stowe wrote: “Now the question is, which is in fault, The Declaration of Independence, or the customs and laws of America as to woman? Is taxation without representation tyranny or not?” In the same vein, Stowe applauded John Stuart Mill’s The Subjection of Women (1869) because of its forthright stand on women having the same natural rights as man. Stowe had, however, a nuanced approach to feminism. She strongly supported women’s right to vote, but she also saw the positive side of domestic duties as a woman. Rather than “free women from the home,” she wanted domestic work to be more prized. When women did enter the workforce outside the home, she wanted them to be paid what a man would be paid for an equivalent job. According to one historian: “[Stowe] disliked frilly feminism and strident feminism.” Man was not the enemy, in Stowe’s thinking, but a co-equal.

Julia Ward Howe’s fame from writing The Battle Hymn of the Republic during the Civil War did open many doors for her as she pursued causes in the latter decades of the nineteenth-century. Both women’s suffrage and pacifism were her dominant interests. Howe’s post-war position regarding women was a complete change from her antebellum point of view. While Howe advocated that women be confined to the “functions of the inner world of home — bearing and raising children,” before the war, her position on women’s rights had completely changed in both words and deeds. In an 1885 speech, she confided, “No one could be more opposed to woman suffrage than I was twenty years ago … Let me say to fashionable women … that the time is coming when suffrage will be fashionable.”

In addition to promoting woman’s suffrage in her writing and speaking activities, Howe joined the organizations actively advocating women’s rights. Aligning herself with the moderate women’s rights organization in 1869, The American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), she became the editor of the organization’s publication, Woman’s Journal. Howe was an active member of the Association of American Women (1876 – 1897), the president of the New England Woman’s Club, the co-founder of the Massachusetts Woman Suffrage Association, the New England Woman Suffrage Association, and the founder of the General Federation of Women’s Clubs in 1893 and its director for five years. To these groups and in the course of her numerous speaking engagements, she brought her considerable visibility and positive image as an American icon when she spoke out on women’s suffrage.

After the war, Clara Barton embarked on an extensive speaking tour of the country. Her initial subject matter was her recollection of being on the battlefields of the Civil War. While on this speaking tour in November 1867, Barton met Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony as she changed trains in Cleveland, Ohio. Barton found herself a kindred spirit with these two leaders of women’s suffrage; she did not need to be convinced to turn her focus on the expansion of women’s rights on the political and social fronts. Barton continued to lecture on her wartime experiences, but she would emphasize what women were capable of accomplishing, using her own life as an example. Here was a woman who was not merely a proponent of women’s rights, but also a practitioner with an impressive history of doing what others were preaching.

Barton’s lectures were advertised in Revolution, the publication of Stanton and Anthony’s association. On several occasions during her lectures, Barton was quick to defend the rights of women when she felt her audience (especially the male members) needed a reminder of women’s rights and the necessity to exercise them. Despite her unqualified agreement with the basic principles of the women’s rights movement, Barton did differ with the position of suffrage as expressed by some feminists. For this reason, she had her name removed as vice president of the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA). She also disagreed with the NWSA position, advanced by Susan B. Anthony, that disapproved of the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment because it gave race precedence over gender for voting rights. Clara Barton firmly believed that Black civil rights should be given priority in the Constitutional Amendment. In Barton’s mind, African American rights took precedence over women’s suffrage. She thought women’s suffrage could be addressed later, after passage of the Fifteenth Amendment.

Sarah Josepha Hale had demonstrated over the years of her editor role at two national women’s magazines that she fervently embraced women’s right to a college education, and for economic, banking, and property rights for women. Hale’s support for women’s rights did not extend to women’s right to vote. Rather than cast a ballot, Hale thought women would do better to advocate for the positions they believed in and use their influence for change.

Sarah Josepha Hale, who for fifty years as a widow and single mother, had written extensively and passionately about the role of women and exemplified the life of an independent professional woman, found herself out of synch with the view of many young women in post-Civil War America regarding suffrage. Hale passed the torch of women’s rights to a new generation of activists who were preparing the way for achieving women’s suffrage in the twentieth-century. Seventy-two years after the historic Seneca Falls Convention and forty-one years after Sarah Josepha Hale’s death in 1879, the Nineteenth Amendment was passed and women were granted the right to vote across the United States.

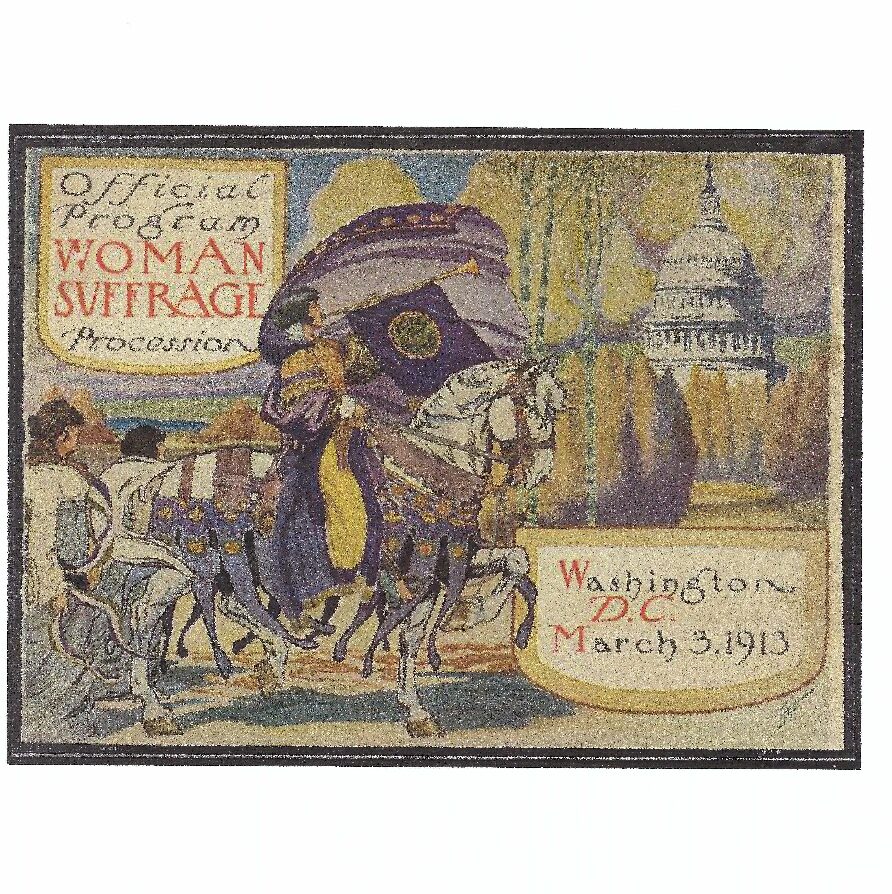

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress collection.

Source from The Better Angels: Five Women Who Changed Civil War America (University of Nebraska Press).

Recent Comments