The Battle of Fredericksburg, Virginia in December, 1862, was to have been the first step in the Federal plan to seize the Confederate capital in Richmond. Senior level officers in the Union Army were convinced that their troops would be spending a victorious Christmas in the capital city. The popular cry “On to Richmond!” was not so much a goal, but an expectation of Union success.

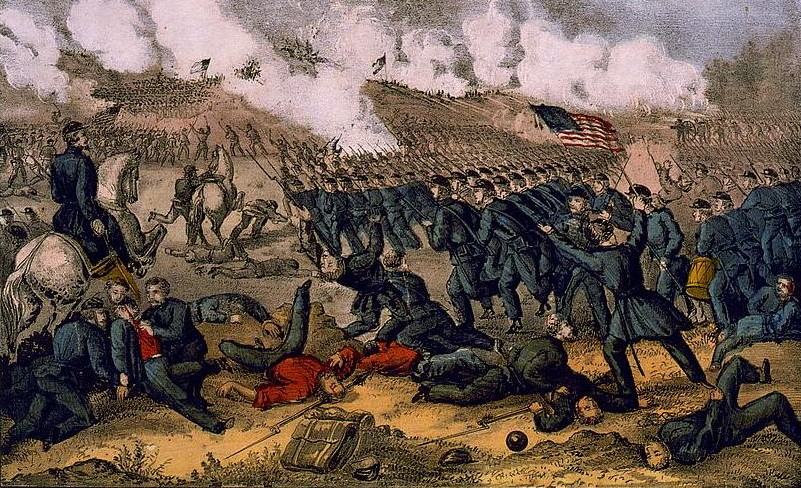

Fighting at Fredericksburg – sixty miles from Richmond – proved otherwise. Employing Napoleonic tactics of charging the enemy in lines of battle proved disastrous. Wave after wave of Union infantry stormed the ground before Marye’s Heights adjacent to the city of Fredericksburg with appalling casualties. As Union troops crossed the open ground leading to Marye’s Heights, they were mowed down by Confederate musket and artillery fire. Confederate artillery commander Edward Porter Alexander promised James Longstreet: “General, we cover that ground now so well that we will comb it as with a fine-tooth comb. A chicken could not live on that field when we open on it.”

In the late afternoon on the day of the battle, the situation was desperate; Union casualties were stacking up in front of the stonewall at the crest of the Heights where Confederates were three rows deep firing continuously from their protected defensive position. Despite the failure of preceding Union attempts, Union Brigadier General Andrew A, Humphreys believed he had the solution – one that brought the essence of Napoleonic military thinking to the attack — a bayonet assault on Marye’s Heights.

Despite his own paucity of combat experience and the fact that none of his Pennsylvania troops had been in battle before, Humphreys oozed confidence. He pointed to the Heights in the distance and announced: “We must gain the crest.” At 4:00 p.m., Humphreys’s men began their advance. Not wanting his troops to break their momentum in the charge by taking time to reload, he required all muskets to be kept unloaded. He wanted to storm Marye’s Heights using bayonets only. Humphreys ordered all muskets to be “rung.” That is, each infantryman was to drop his ramrod down the barrel of his musket, and the resulting clanging sound would verify that the firearm was empty.

Humphreys, brimming with bravado, rode among his troops listening for the telltale ring of empty muskets, waving his hat in the air, exhorting his division to: “Give them the cold steel! That’s what the rascals want!” Later Humphreys would embellish his description of the battle scene: “[The] setting sun shining full on my face gave me the aspect of an inspired being.” Humphreys had two horses shot from under him during the battle. The general was not hit, but his troops were not as fortunate. His division lost 1,000 of its 4,500 men in an hour of fighting.

Confederate General James Longstreet reported after the battle about the Union effort: “No troops could have displayed greater courage and resolution than was shown by those brought against Marye’s Heights, but they miscalculated the wonderful strength of the [Confederate] line behand the stonewall.”

Text based on Your Brother in Arms: A Union Soldier’s Odyssey, University of Missouri Press, 2011.

Contemporary drawing of General Humphreys’s charge, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Recent Comments