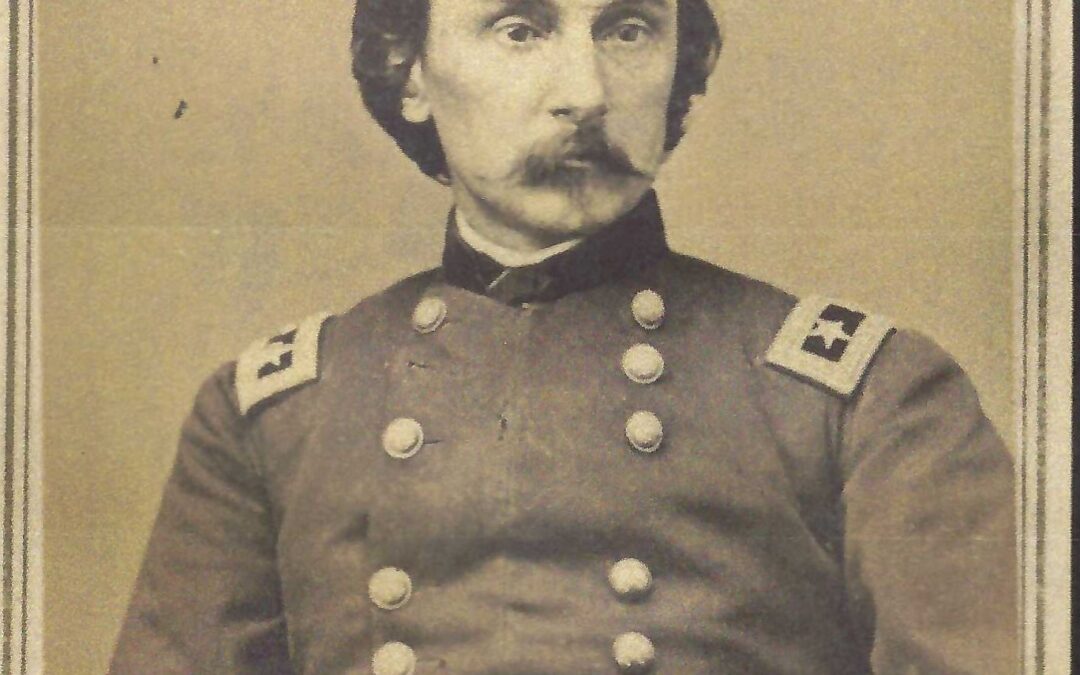

Why did a bright, young man who was consistently at the top of his class at West Point and who was credited with rescuing the Union Army “from imminent peril” at Gettysburg in 1863, plummet to being called “a very loathsome, profane, ungentlemanly and disgusting puppy” by the provost marshal of the Army of the Potomac at the end of the Civil War? Once considered a “rising star” of the Union Army in 1864, Warren ended the war at the Battle of Five Forks being called a “reluctant warrior” by Ulysses S. Grant.

Young Gouverneur Warren entered West Point in July 1846 and quickly demonstrated his aptitude for science and mathematics; throughout his time as a cadet, he was in the top ten percent of his class academically. Upon graduation, Warren became an engineering officer and proved to be a gifted topographical expert in his field assignments. As the Civil War unfolded, Warren took on increasing responsibilities as an engineering staff officer. He quickly rose to Chief Engineer of the Army of the Potomac serving under General George Meade at Gettysburg.

On July 2, 1863, Brigadier General Warren rode to the Union signal station at the top of Little Round Top to observe the battle taking place below the summit in the wheat field, peach orchard, and Devil’s Den. Scanning the adjacent Big Round Top next to him with his field glasses, a surprised Warren saw the glint of gun barrels and bayonets carried by General John Bell Hood’s Confederate troops. Quickly realizing that the Rebel troops on the wooded hillside were moving to flank the left of the Union line and gain the high ground on the Two Round Tops, Warren ordered a Fifth Corps brigade that had just arrived in the area to occupy and defend Little Round Top. Seeing that the brigade of only four regiments was insufficient to defend the summit against Hood’s troops, Warren – a staff officer with no fighting unit command authority – persuaded Major General George Sykes, commander of the Fifth Corps, to release his Third Brigade to defend Little Round Top. Sykes complied. Despite repeated Confederate assaults, the Union line held, thereby denying Hood’s Rebel force from taking the key ground. At dusk, the Confederates withdrew from the Round Tops.

Warren’s decisive actions at Little Round Top were praised by senior officers. When Union General Winfield Hancock was wounded at Gettysburg, Warren was named as his replacement commanding the Second Corps of the Army of the Potomac. No longer a staff officer, Warren now had command of fighting troops. This was a significant achievement. His leadership skills were next put to the test in October 1863 when his Corps trapped the Confederates at Bristoe Station, Virginia. Dealing a significant blow to General Henry Heath’s Confederate force, Warren’s men launched a critical surprise assault that resulted in 1,360 Rebel casualties compared to 350 casualties in the Union Second Corps.

Not only did Warren demonstrate his battle leadership and courage on the field, he also evidenced his unwillingness to expose his troops to unnecessary risk of enemy fire. In late November 1863 Warren’s troops, as part of the Army of the Potomac, faced the Confederates at Mine Run, Virginia. Dug in across a broad, deep, and frigid creek, the Confederates held the high ground. Union troops facing the enemy were so pessimistic about their chances of surviving an assault they pinned slips of paper with their names on their uniforms so they could be identified after what was considered a suicidal undertaking.

On dawn of November 30, General Warren assessed the situation his troops would face charging up the steep hill toward the Confederate lines. He calculated that it would take his troops eight minutes to ford the waist-deep stream and mount the hill leading up to the Confederate lines. For eight minutes they would face withering fire over open ground. Warren sent a staff member to Meade to recommend that the assault be called off. Meade went to the proposed assault site and after reviewing the situation he agreed with Warren and called off the planned attack. Later, in a letter to his wife, Meade reflected on his decision at Mine Run: “I would rather be ignominiously dismissed and suffer anything, than knowingly and willfully have thousands of brave men slaughtered for nothing.”

As Grant’s Overland Campaign started in the spring of 1864, Warren was given command of the Fifth Corps of the Army of the Potomac, continuing to serve under General George Meade. The Army of the Potomac now reported to General Ulysses S. Grant who, effective March 12, 1864, was commander of all the Federal Armies. Grant, unlike his predecessor, chose to lead the armies from the field, not from an office in Washington City. At this point in the war, General Warren was considered a rising star in the Union Army. However, his reputation began to flounder as the campaign opened in the Wilderness of Virginia. Warren hesitated to attack in the dense woods where his Fifth Corps was entangled. He feared his right flank was unprotected and vulnerable. Meade pressed Warren to attack and finally the Fifth Corps clashed with the Confederates at Saunders’ Field. After two days of intense fighting in the Wilderness, the result was 18,000 Union and 12,000 Confederate losses. In his Memoirs Grant reported: “More desperate fighting has not been witnessed on this continent than that of the 5th and 6th of May [1864].”

The Army of the Potomac pressed on to Spotsylvania Court House and General Warren was directed to engage the Confederates along the heights near the Spindle Farm at Laurel Hill. On May 8, Warren’s men fought the amassed Confederate Army – infantry and cavalry – with Warren riding among his men to urge them on. Heavy Union loses resulted. On May 10, Warren made a second attempt to take the Rebels dug in at Laurel Hill. Again, the Union was pushed back with heavy losses. Two days later, Meade ordered Warren to lead his men back to Laurel Hill and overrun the Rebel entrenchments. Warren told Meade that another attack would be fruitless. An enraged Meade ordered his Fifth Corps commander to attack at once, “at all hazards with your whole force, if necessary.” Warren followed orders and attacked. His divisions were raked by heavy Confederate fire. One of the men in these divisions described the attack later as a Union “slaughter pen.” Both Meade and Grant saw Warren’s reluctance as a weakness, 18,400 Union casualties at Spotsylvania Court House notwithstanding. For the remainder of the Overland Campaign, Warren was on Grant’s black list.

Grant, in his Memoirs, gave Warren a left-handed compliment: “There was no officer more capable, nor one more prompt in acting, than Warren when the enemy forced him to it.”

General Warren served without further run-ins with Meade or Grant through the balance of 1864. In the spring of 1865, a new player came on the scene that caused the fragile state of Warren’s relationship with his superior officers to be irreparably damaged – Cavalry General Philip Sheridan. A feisty, vainglorious West Point graduate who, like Warren, was a native of upstate New York.

By the end of March 1865, Grant was eager to crush the Army of Northern Virginia that was showing signs of weakness as it struggled to maintain its defensive lines around Petersburg, Virginia. Grant looked to stretch the siege line at Petersburg and seize the South Side Railroad that was the tenuous lifeline of supplies for the Army of Northern Virginia (as well as the civilian inhabitants of Petersburg and Richmond, Virginia.) Grant sent the newly-arrived Sheridan and his cavalry – fresh from a successful campaign in the Shenandoah Valley –to attack the Confederate’s right with the support of Meade’s infantry. Sheridan wanted the Sixth Corps to support him, but Grant and Meade thought the Fifth Corps under Warren was closer to where the infantry support was needed and could provide a rapid response in the vicinity of Five Forks, Virginia.

Due to poor battlefield intelligence regarding the location of Confederate troops provided by Sheridan’s cavalry, Warren’s three divisions were misdirected and required immediate realignment. Warren rode off to direct the division that had gone too far north. Meanwhile, the other two Fifth Corps divisions maneuvered to flank the Confederate lines. Sheridan was furious about the battlefield confusion demanding to know: “Where is Warren?” By late afternoon the two Fifth Corps divisions had flanked the Confederate line and the errant third division, redirected by Warren, had joined the battle and caused the Confederates to retreat. In the meantime, in the fog of battle and fumbled communications, Grant authorized Sheridan to relieve Warren of command and order him to report to Grant for reassignment.

Warren argued his case with Sheridan, Meade, and Grant, but his request to be put back in command of the Fifth Corps was unanimously rejected. Despite Warren’s extraordinary efforts to bring his misdirected division back into the battle (misdirected by faulty battlefield intelligence from Sheridan’s cavalry) and having his horse shot out from under him during the Battle of Five Forks, Warren was judged a “reluctant warrior” by Grant, his acolyte Sheridan, and the deferential George Meade.

Warren resigned from the Army in June 1865 and then took on civilian topographical and engineering assignments in the Midwest states. For the remainder of his life, he sought vindication for the action taken against him at Five Forks. On November 21, 1882 – seventeen years after the Battle of Five Forks – Warren was vindicated by a federal court of inquiry. This vindication came three months after his death.

A close friend and fellow engineering officer, Henry L. Abbot, said of Gouverneur K. Warren after he died: “It is pitiful that one of his last requests was to be laid in the grave without soldierly emblems on his coffin or uniform upon his body. “

Today, visitors to the Gettysburg Battlefield can see the imposing statue of Warren standing on Little Round Top, field glasses in hand, representing the highwater mark of the General’s military career. Perhaps, over time, Warren’s true heroism has now prevailed.

Photo of G. K. Warren courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Source: Your Brother in Arms: A Union Soldier’s Odyssey by Robert C. Plumb; Happiness Is Not My Companion by David M. Jordan.

Recent Comments