“To the friends of missing persons: Miss Clara Barton has kindly offered to search for missing prisoners of war. Please address her at Annapolis, Maryland giving name, regiment, and company of any missing prisoner.” – Abraham Lincoln, 1865

As the Civil War was winding down, Clara Barton took on another cause: accounting for the thousands of missing Union soldiers. Initially rebuffed in her attempts to locate the missing because it was considered not a proper role for a woman, Barton sought help from the top – the President of the United States. Grief-struck when Lincoln was assassinated, Barton, nevertheless, moved forward with her search for the missing. Using her own funds at the start, she established Friends of the Missing Men of the United States Army, employed assistants and purchased the necessary materials to help communicate with the families of the missing.

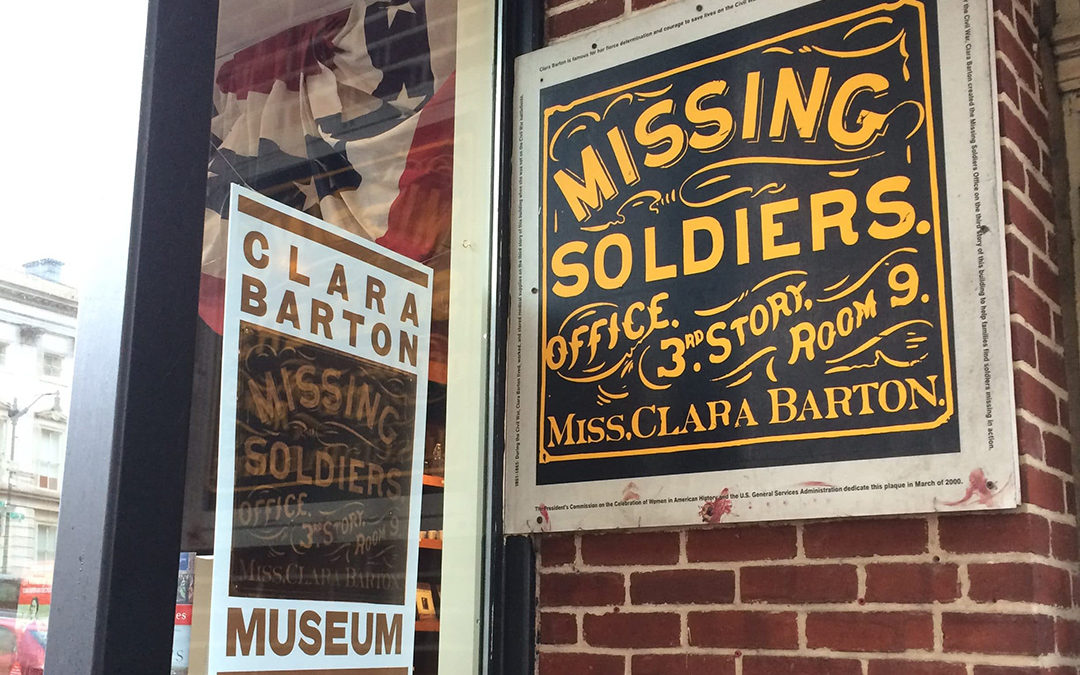

Barton established a Missing Soldiers Office at 437 7th Street in Washington, DC and began to doggedly track down the whereabouts of missing soldiers. She was helped by Dorence Atwater, a former prisoner-of-war at Andersonville Prison, who helped Barton gain access to information and locations barred to her because of her gender.

Fortunately, her friend, Francis D. Gage, helped Barton petition Congress to appropriate fifteen thousand dollars to underwrite her work with missing soldiers. Now with funding, the Missing Soldier’s Office was able to send 300 letters per week to engage the families of the missing in the search. Between 1865 and 1868, 63,000 letters were sent, resulting in 22.000 Union missing soldiers being identified. By the late 1860’s, Barton’s attempts to locate the missing began to wind down. The office on the third floor of 437 7th Street was closed down and items packed away in storage.

Then, as a result of the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire and stepped-up fire safety measures across America, the third floor was boarded up to comply with new building codes. (The bottom two floors continued to be rented for commercial and professional use.) In 1996 a General Services Administration (GSA) employee visited the 437 7th Street location to assess the building in preparation for a planned demolition in conjunction with an urban renewal project. During his inspection, the GSA employee found letters and objects stored after the Missing Soldier’s Office closed. Among those objects was a sign: “Missing Soldier’s Office, Office 3rd Story Room 9, Miss Clara Barton.”

Thanks to the observant GSA employee and his belief that what he discovered was historically significant, demolition was cancelled and after two decades of restoration, the 3rd floor was turned into the Clara Barton Missing Soldier’s Office Museum. Clara Barton’s office is now open to the public under the auspices of the National Museum of Civil War Medicine.

Recent Comments